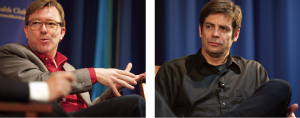

Reason magazine editors Matt Welch (left) and Nick Gillespie

(right) try to establish a libertarian beachhead in a liberal town

photo: Ed Ritger

(right) try to establish a libertarian beachhead in a liberal town

photo: Ed Ritger

The libertarian viewpoint is a mix of fiscal conservatism and social liberalism. That’s the way that Nick Gillespie, editor of Reason magazine, defines it, and that is where a lot of Americans seem to be in their actual beliefs. So why don’t people vote for the Libertarian Party?

Last year, I asked political humorist P.J. O’Rourke why he had once criticized the Libertarian Party – agreeing with many of their positions but noting that they often went off into crazyland with proposals to privatize sewers and whatnot. “The Libertarian Party platform just isn’t electable, because essentially you’re standing up and saying, ‘I can give you less of everything.’ You may get a few voters, but I don’t think you’re going to get them all,” O’Rourke said.

“I don’t have a problem with libertarianism,” he added. “I really do agree with them about almost everything. But I think there’s a tendency in libertarianism to apply an excess of rationalism to politics; more than it can stand. Politics is not simply a rational activity. And the tendency of libertarians is to regard it as though it were simply a rational activity, as if it were a calculus or a spreadsheet or something. There’s much, much more to it than that. I think they leave out that side of things.”

On July 22, Reason’s Gillespie appeared on HBO’s Real Time with Bill Maher, in which he acted like … what’s a word I can use in print? Perhaps a jerk, let’s say. For example, when fellow panelist and Braddock, Penn., Mayor John Fetterman said he was the mayor of the poorest town in his state, Gillespie shot back, “You must be very proud.”

That’s not exactly a comment that would counteract the general perception libertarians don’t care about the less well off. So I had a bit of trepidation about Gillespie’s trip to San Francisco the following week to speak at The Commonwealth Club with his fellow Reason editor, Matt Welch.

I needn’t have worried. Gillespie and Welch did a fine job explicating their views, providing the provocative statements expected of libertarians while not saying too much that you’d be ashamed to have your parents hear.

In fact, Gillespie said one of the most typically libertarian things during a discussion of federal spending: “The big money is in military, Medicare and Social Security. It’s not hard to find fat. We have doubled military spending, basically, since 2001. We have nothing to show for it other than a lot of spent money.”

The challenge would seem to be selling that message to a country that (a) loves its military, and (b) is addicted to middle class entitlements. As P.J. O’Rourke said, it’s hard to tell people you’ll give them less of everything.

But Gillespie wasn’t a burn-the-villages libertarian who refused to make any concessions to society; he parted with such people when he told us, “We believe in a governmentally provided social welfare safety net.” And Welch was blunt about his social liberalism: “I absolutely do not for one second understand opposition to gay marriage.”

If Gillespie is correct and the ranks of libertarians have swelled with independent voters and young people who are disaffected by the two-party political system, we can probably expect to see more variations in beliefs among the libertarian thought leaders. There are many different kinds of libertarians, ranging from followers of the antireligious Ayn Rand to evangelical libertarians, from people who are absolutist antigovernment types to people who just want to shrink the size of government.

San Francisco might be far more libertine than libertarian, so it’s not a good place to judge the popularity of small-government politics. But we can see around the nation that libertarians are enjoying their moment in the spotlight.

But just as this city isn’t an ideal control group, so too is today not the ideal era to get long-term traction. That’s because we’re in the midst of a severe economic scare – maybe we can even call it a panic, like they did in the 19th century before government policy smoothed out the highs and lows of our economy.

That means many people are more open to outsider political movements in times of crisis than they are when things are going smoothly. In calmer times, people might be just as disaffected by the two-party system, but they’re also relatively comfortable, so their reaction is simply not to vote. But during crisis, they are far more likely to be incited to head to the polls, and their allegiance to any candidate or party cannot be taken for granted.

Give Gillespie a few more years and maybe we’ll learn if his politics are gaining long-lasting adherents, or if it was just be a brief flirtation that Americans experienced when they were drunk with panic.

John Zipperer is a San Francisco-based writer and editor. E-mail: johnz@northsidesf.com.