| |

|

How to fool the Nazis ... almost

By Sharon Anderson

The Forger’s Spell: A True Story of

Vermeer, Nazis and the Greatest Art Hoax of the Twentieth Century

by Edward Dolnick

Psychology and manipulation are the prominent themes in Dolnick’s latest book, a follow-up to his award-winning The Rescue Artist, which is widely considered the best book ever written on art crime. Psychology and manipulation are the prominent themes in Dolnick’s latest book, a follow-up to his award-winning The Rescue Artist, which is widely considered the best book ever written on art crime.

The compelling and dramatic stories surrounding World War II and the Nazi regime are well known. Most of us are familiar with the stories of the Nazis’ pillage of Europe’s galleries and museums. Dolnick’s new book shows the extent to which the Nazis were obsessed with looting fine art. The art sanctuaries of Europe were ransacked in regimented fashion, complete with “wish lists” of artists they intended to confiscate in advance.

Enter Han Van Meegeren, a Dutch painter who, though he possessed less painterly skill than entrepreneurial spirit, still managed to pass off his own works as original paintings by Johannes Vermeer. Among his clientele: Hermann Goering and Adolf Hitler.

The life of Johannes Vermeer is still shrouded in mystery. Little is known about this famous artist, and even his appearance remains a secret. This is, as Dolnick points out, troubling for art historians, but a gold mine for a forger.

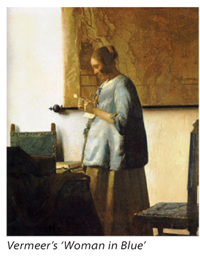

Having studied art and architecture in Vermeer’s home town of Delft, van Meegeren lived a life of indulgences. He had an extremely large home in the cramped urban spaces of Amsterdam where he painstakingly studied the techniques of the old masters and perfected his deceit. Blue gowns, bodices, interiors shrouded in darkness and pearl drop earrings – the trademarks of Vermeer – found their way into van Meegeren’s paintings, convincing art collectors and dealers alike that they had stumbled upon unknown masterpieces.

Dolnick quotes a famous line from a Thurber novel: “Mere proof won’t convince me.” This statement deftly encapsulates the entire con. Van Meegeren understood from the start that the Nazis and Goering in particular felt a profound sense of personal entitlement to have the best of everything. Far from an art expert, van Meegeren was able to use this simple psychology for his own gain.

The war ended, and naturally van Meegeren wanted to distance himself from the Nazis so as not to be viewed as a sympathizer. Strangely, his imitations were so convincing to the art world at large that after he confessed to the forgeries, no one in a position of authority believed him at first.

Similarly, art historians create careers out of their assessments of great masters. These assessments become doctoral dissertations, and the resulting scholastic acclaim turns into a career. When an old master is analyzed and determined to consist of newer pigments than would seem appropriate, academia is the first to doubt the evidence.

Goering and Hitler wanted the finest personal art collections in the world. Simply put, van Meegeren knew what they wanted to believe and pandered to those expectations. Millions of dollars exchanged hands in the wartime art world and, at one point, Goering traded 147 paintings from his collection for a single Vermeer – a Vermeer from the collection of none other than Han van Meegeren.

He almost got away with it.

Sharon Anderson is a painter and writer living in Los Angeles. She has upcoming exhibitions in New York City and Vienna.

|

|

|

|