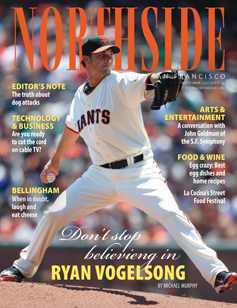

From left: cameraman Mike Charlton, armored car driver Teo Stanic,

correspondent Joel Brand, and the author pause on Mount Igman

before driving through a Serb sniper zone en route to Sarajevo

correspondent Joel Brand, and the author pause on Mount Igman

before driving through a Serb sniper zone en route to Sarajevo

In my stupor of sleep, a 2,000-pound bomb exploded in the Dinaric Alps and woke me up. I liked hearing the sound of democracy in action. Cameraman Mike Charlton was at my door smiling: “Looks like Johnny Serb is in for it, mate.” Mike hadn’t slept, and he had already been filming the NATO attack on the Serb positions in the mountain range that surrounded the Bosnian capital. Sarajevo sat on a valley floor, making civilians and soldiers easy prey for Serb gunners. Richard Holbrooke had seen the United States debacle in Vietnam and knew that sometimes a judicious use of force was the only way to go. He had also chastised European allies, calling Bosnia “the greatest collective failure of the West since the 1930s.” Strong words, soon to be followed by strong actions. The Clinton administration (rumored to have a focus group on just about everything), knew there was no public tolerance for American boots on the ground in Bosnia. So with the help of satellite technology, Holbrooke made a bombing list and went after legitimate Serb targets: command and control centers (officers’ quarters and communication centers), anti-aircraft missile batteries, and soldiers’ barracks. We even saw the infamous Lukavica sniper barracks get blasted by an ever-so-slow A-10 Warthog. Serb air defenses had been eviscerated. Holbrooke had to keep the bombardment plans away from Greek NATO members, who would have told their eastern Orthodox Serb brothers (like they did in 1999, when they fed bombing targets to Serb commanders in Kosovo). A year earlier, the United Nations NATO response to a previous attack on the same market was anemic. But not on Holbrooke’s watch; he was successful – we heard the fighter-bombers racing overhead almost piercing our ears. We saw the Serb anti-aircraft position behind our hotel shoot rounds at United States jets, and then we saw two bombers dive and blast the position to smithereens. Before going back on the streets, we had to wait until sunrise and for the curfew to end. It was quite a site to see the Serb positions smoldering in the mountains above the city. Sarajevo’s streets were joyous, and we saw smiles we hadn’t seen before from the citizenry. We picked up our correspondent, Joel Brand, from a colleague’s flat in downtown Sarajevo. He was ecstatic, having seen Bosnians get blasted for years: “We were screaming out the window, ‘Go! Go!’ The whole neighborhood was, too!”

We put our reporter on the satellite for debriefing by our anchors in Los Angeles, and then went out to shoot a story on the bombing. Because most Serb anti-aircraft defense had been knocked out the night before, we could see and hear FA-18 Hornets and A-10 Warthogs blasting targets all day long. The West had finally stepped up and said no to Serbia’s Slobodan Milosevic. And it was the work of one man who had seen the United States military might fail in Vietnam, and he knew how to be successful here in Bosnia: Richard Holbrooke. Holbrooke then began the cat-and-mouse game of negotiating with Milosevic, shuttling from all over Europe to the Serbian capital of Belgrade. Holbrooke had done a lot of work in the Balkans getting the Yugoslav National Army out of Bosnia (the army had left their weapons for the Serb irregulars, Chetniks, who made Sarajevo a living hell). He looked the other way when Islamic countries like Iran sent weapons and soldiers to the theater, and when the Germans armed the Croatian forces, which had successfully forced tens of thousands of Serb soldiers from their land in the Krajina in 1995. Holbrooke leveled the playing field despite a United Nations arms embargo.

No wonder there were so many arms peddlers at the Esplanade Hotel bar in Zagreb, Croatia, our stopping point before heading to Bosnia. The air strikes also emboldened the Bosnian Army, which advanced on Serb positions not only around Sarajevo but also all over the country. Holbrooke had learned from Vietnam that the United States had to have a good ally, and even more important, a just cause. United States policy had both in Bosnia, unlike in Vietnam where United States allies were as corrupt as they were inept (Holbrooke’s blunt and pessimistic assessments of United States policy in Vietnam were part of the Pentagon Papers that Daniel Ellsberg leaked in 1971).

The curfew had been relaxed, so nightly, we’d hang out at an old Turkish fort above Sarajevo and watch our tax dollars at work pounding Serb positions. A United Nations radar site manned by British troops was nearby, and they would give us hot tea and laugh at the situation because the Serbs had shot at them, too.

Almost daily, Holbrooke would meet with Milosevic in Belgrade to get him to move back what was left of the heavy weapons to 12.5 kilometers from Sarajevo. Holbrooke wasn’t your typical diplomat (nicknamed by some the raging bull of United States diplomacy), and he didn’t do double speak. He saw peacekeeping as a robust way to slap aggressors into submission. He wouldn’t mince words like the United Nations and European diplomats tried to do with Milosevic, but failed while the Bosnian body count rose and the term “ethnic cleansing” became commonplace. But that’s not to say Holbrooke wasn’t cagey; he and NATO were out of targets by the time the Serbs had capitulated and agreed to move back the heavy weapons. Milosevic also agreed to cease fire in Sarajevo (but not the rest of the country) and to peace talks. Unlike Vietnam, he had bombed the enemy into submission.

Back in Sarajevo the cease-fire held, and the first front of the war across the street from our hotel was silent. We had heard that Bosnian troops were advancing on Bihac in northwestern Bosnia. Bihac had become a bloody shooting gallery with a Bosnian Muslim warlord switching sides to join the Serbs. Beleaguered Bangladeshi United Nations peacekeepers were shelled daily and had no winter gear to fend off the chilly Balkan weather. In western Bosnia, Bosnian troops were closing in on the ethnically cleansed city of Banja Luka.

We asked our bosses in Los Angeles if we could go to Bihac, but the answer was no; the attention span of our audience regarding Bosnia was spent, and it was getting too expensive to keep us in Sarajevo. We saw off several colleagues en route to Bihac, and once again the upper floors of the Holiday Inn became a celebration.

As we left Sarajevo, our usually stoic Croatian armored car driver, Teo Stanic (the best driver in the former Yugoslavia), was smiling ear to ear. The war was winding down and everybody knew it, especially one Richard Charles Holbrooke. Matt McFetridge is a two-time Emmy Award-winning television producer who has covered 20 wars in 20 countries over 20 years. E-mail: matt@northsidesf.com