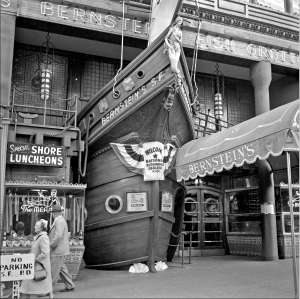

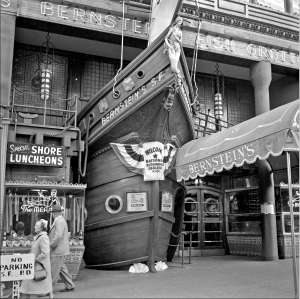

The entrance to Bernstein’s Fish Grotto at 123 Powell was a faithful reproduction of Columbus’s flagship, the Nina. The location is now a shoe store.

We should mourn our losses. Personally, I mourn for Bernstein’s Fish Grotto, Original Joe’s, Trader Vic’s, Jack’s, Ernie’s Restaurant, Veneto’s, Clinton’s Cafeteria, the Bay City Grill, the Poodle Dog, and Vanessi’s, among others.

But a few treasured institutions remain. They exist in a time warp. Is anything more satisfying than a good time warp? Tadich Grill, Swan Oyster Depot, Fior d’ Italia, the Cliff House, Sam’s Grill, Schroeder’s, the House of Shields, the Old Clam House, and the Garden Court in the Palace Hotel. Maybe a few others.

Certainly this isn’t a comprehensive list of San Francisco’s best restaurants past and present. Add some of your own if you wish.

Here are a few of my classics – long gone or still around.

Bernstein’s Fish Grotto

One of my memories as a toddler in San Francisco is of grand walks with my folks downtown on Powell Street and the fantasy that we were embarking on an ocean voyage. Our ship was called Bernstein’s Fish Grotto. Its wooden prow, complete with brass-rimmed portholes, jutted onto the sidewalk and faced the clanging cable cars. We went to Bernstein’s for Dungeness crab cocktails with red sauce. Those were the years of the Great Depression, but I was unaware of it. Later I realized that times had been hard, and my father was frequently out of work. Bernstein’s opened in 1912 and finally closed in 1981.

Original Joe’s

I always thought that restaurants were theater and provided theatrical experiences. Consider Original Joe’s, which opened in 1937 and finally was closed by a fire in 2007. Owners anticipate reopening.

When I was a lad my folks patronized this Tenderloin classic. It was brightly lighted with a long counter along one side of the room and booths along the other. We always sat at the counter. That’s where the action was. Behind that counter and running the full length of the room, was the open kitchen, all cooking stations in a line. To the far right was the broiler and grill. To the left ran the waist-high stovetops with ovens below. That was where the most dramatic scenes played out.

White-jacketed cooks sautéed orders in round shallow pans. Waiters wore tuxedos. My mother thought one young waiter with a full mop of carefully coiffed, curly gray hair was handsome and so commented each time we dined there. My father always responded that the man had dyed his hair. The waiter knew us and anticipated our orders. For my father it was usually roast beef, medium rare. My mother favored veal Marsala and chicken sauté. I was a meat-balls-and-spaghetti kid. We ordered mixed vegetables as a side dish – spinach or chard, zucchini, carrots, broccoli, and cauliflower. The cook took one of those shallow pans, poured in a generous splash of olive oil and set it on the burner. Flame licked the sides of the pan. Then he grabbed a fistful of vegetables and tossed them in the hot oil along with a spoonful of minced garlic, kept the hot pan moving over the flames and once or twice raised it and flipped the vegetables. Pure theater.

The Cliff House

Sometimes my father and I went by streetcar out to Land’s End where he shared his passion for mid-winter swimming by taking me to Sutro Baths – a massive, glass-enclosed, Victorian amusement center where we paddled around in one of several heated saltwater tanks. After our swim, we went to the adjacent Cliff House for clam chowder and stared out at the fog-bound Pacific.

Both the Cliff House, which opened in 1863, and Sutro Baths in 1881, were creations of Adolph Sutro, wealthy, Comstock Lode mining engineer and later San Francisco mayor. Fire destroyed the first Cliff House in 1894, and Sutro rebuilt it as a Victorian chateau. It survived the 1906 earthquake and fire only to burn to the ground the following year. In 1909 it was rebuilt in a simple, neoclassic style and became a San Francisco landmark. Sutro Baths burned down in 1966. The Cliff House is still operating at the original location.

Trader Vic’s

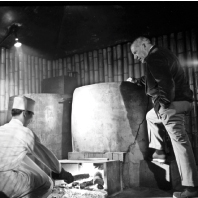

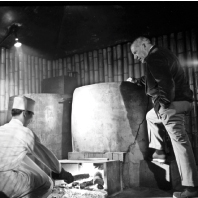

Vic oversees a Chinese oven used to cook his Indonesian lamb roast and barbecued spareribs

Victor Bergeron Jr. was an ambitious, young knockabout with a wooden leg and an irrepressible spirit, who opened a saloon-restaurant in a wooden shack on San Pablo Avenue in Oakland in 1934. He went on to become an international celebrity just like the clientele that later favored his San Francisco restaurant, Trader Vic’s.

Bergeron was born in San Francisco in 1902, the son of a French-Canadian waiter and a French woman from the Pyrenees. When he was 6, an accident left him with tuberculosis of the knee, and his left leg was amputated.

In 1934, Prohibition had just been repealed, and people were thirsty. Times were hard, and Vic served cheap but good food and drink. He called the funky venture Hinky Dink’s for the World War I tune, “Mademoiselle from Armentieres,” which had a line, “hinky-dinky parlez-vous.” Soon San Franciscans were finding their way to Vic’s Oakland dive.

In those days Vic, was a gregarious, salty-mouthed, high-spirited scamp with a strong sense of fun. He poured outrageous drinks, sang in a gravelly voice and did card tricks. On occasion he came out from behind the bar, gained the attention of his customers and stuck an ice pick in his wooden leg. He was fond of saying, “Don’t ever get one of these things unless you really need it.”

By 1937 Vic decided to go Polynesian. Funky-rustic morphed into funky-South-Sea-Islands with shrunken heads, ship models, fishing nets, and other real and contrived artifacts. Trader Vic’s stretched out with a new cuisine – a Cantonese-Polynesian hybrid that gave Vic an opportunity to expand his repertoire of exotic drinks, most based on rum and strong enough to peel the paint off the walls if there had been any.

It wasn’t until 1951 that Vic opened in San Francisco. He found a tin-roofed garage on Cosmo Place between Taylor and Jones. The shed – for that’s what it was – featured Vic’s trademarks: lush tropical plants and glass cases with South Seas artifacts, and yes, a shrunken head.

The Sanciminos in front of their

family restaurant

Skilled barmen dispensed powerful, Vic-created rum drinks like the legendary Mai Tai, the Sufferin’ Bastard and the Missionary’s Downfall.

The food was great: barbecued spareribs, crab Rangoon, bongo bongo soup (an unctuous puree of oysters and spinach), and Indonesian lamb roast with Javanese sate sauce.

Soon the tin-roofed shed was receiving international publicity. The more famous the restaurant became, the more it attracted the highly affluent social set. U.S. presidents, movie stars, sports figures, authors, opera stars, locals from old families, debutantes, college students and their dates, all flocked to Trader Vic’s.

As Vic gained personal fame he moved from irrepressible to irascible. He was prickly, profane, gruff, and at times, even charming. But the more he exhibited a rough manner and sometimes shunned his prominent guests, the more they flocked to his restaurant.

Victor Jules Bergeron Jr. died in 1984 but Trader Vic’s in San Francisco went on without him. It finally closed in 1994. The times they were a changin’.

Swan Oyster Depot

Salvatore Sancimino cracks crab at

Swan Oyster Depot

Ah, Swan. Itdates back to 1912 when four Danish brothers opened a small, narrow sautohop where those inclined sat at a white marble counter and slurped oysters. It was on Polk right off California and is still at the same location. The brothers named it Swan Oyster Depot because in Scandinavia the swan traditionally has been a symbol of good luck and prosperity.

But it was an Italian immigrant family that brought to life the glory years of Swan.

One offspring of that family, Salvatore Sancimino, was born in San Francisco in 1919. He graduated from Galileo High School in 1937, and then ran errands for the Bank of Italy before joining the Navy. Following his discharge in 1984, he and three cousins purchased Swan Oyster Depot. He bought them out a few years later.

Sancimino and his wife, Rose, lived in North Beach and began a family that grew to six sons and a daughter.

Today the Sancimino brothers operate Swan Oyster Depot, where they once worked as kids for their father, who died in 1989.

Walk into Swan Oyster Depot now and you will find several of the brothers, frequently joined by their own offspring, behind the counter cracking crab, shucking oysters, serving chowder, or filling orders for home delivery.

Those who drop in for a bowl of chowder or some oysters or to take something home for dinner – perhaps a piece of fresh halibut or that elegant local sole called petrale – become “family” and are treated as such. Early strict family training has obviously paid off. The Sancimino brothers, indeed the entire shop, appear to have been sealed in Saran Wrap in gentler, more salubrious times and unwrapped today for our pleasure.

Isn’t it great to live in a city that really gives a damn about its restaurants?

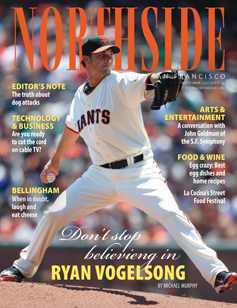

Ernest Beyl is a North Beach writer and, obviously, an eater. E-mail: ernest@northsidesf.com