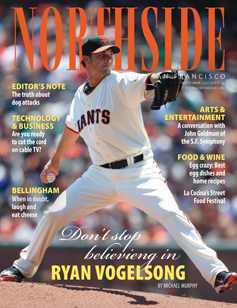

Dr. AimeeChagnon in June

en route to assist Haiti

earthquake victims,

where unfortunately she says

not much has changed since

her first trip in February

photo: Rene Persaud

In 2007–2008, Sebastian Junger and his photographer, Tim Hetherington, took five trips each over 15 months to eastern Afghanistan to be embedded with Second Platoon of Battle Company of the 173rd Airborne Brigade (U.S. Army).

The Korengal Valley is on the Pakistani border. It’s the pipeline for al Qaida-trained foreign fighters and Pakistani Taliban to enter Afghanistan and fight NATO and U.S. troops. Junger spent most of his time at a remote outpost called Restrepo (named after Second Platoon’s beloved, killed-in-action medic Juan “Doc” Restrepo) that plugged into the Afghan War like a main circuit cable. It’s a “tip of the spear” assignment (in military-speak, meaning lots of firefights with the Taliban and al Qaida, and lots of casualties).

Junger has written a book about his experience,

War (Twelve Books), and he and Hetherington directed and produced a Sundance Film

Festival award-winning documentary,

Restrepo. I caught up with Junger via e-mail.

Northside S.F.: I was taught journalism by former Vietnam correspondents, who said they were free to go anywhere during that conflict with no rules except: “First, you don’t jeopardize anyone’s life, and second, you don’t divulge operational details.” A lot of these Vietnam correspondents aren’t fans of today’s embedding [in Iraq and Afghanistan], saying it opens the door to censorship and stricter ground rules.

What do you have to say to that, and would you have been able to write

War if you weren’t embedded?

Junger: There was no difference at all from Vietnam. I was never censored, no one ever asked to look at my material, and there were no constraints on me whatsoever. I would not have been able to write the book if I weren’t embedded because it’s the only way to be with a unit of soldiers.

Northside S.F.: I was in Jalalabad in 2005 en route to Tora Bora and embedded with the 82nd Airborne in Kandahar, but the IEDs (roadside bombs), firefights and Taliban presence were minimal back then.

You were in Korengal Valley for a year, which is a much hairier place. Why Korengal, which U.S. troops call the most dangerous place on earth? Did you have a chance to pick or request which unit you were with?

Junger: I had no idea what the Korengal was, I just happened to be put with Battle Company, and that was where they were sent.

Northside S.F.: How close did you grow to the soldiers you were covering? Did they ever think of politics, or is it just survival? You saw combat by day and night – which is worse?

Junger: Not much night combat, mostly day and dusk. The soldiers never talked about politics – neither did I at their age, it’s really not relevant to their situation. And yes, I got very, very close to them.

Northside S.F.: What about your documentary, Restrepo – how has that been received and how different was producing that compared to writing War? Can you please give the Restrepo backstory – who he was, and what he means to the men you were covering?

Junger: Restrepo has broad distribution and has gotten excellent reviews. We edited by consensus, which is obviously different from writing a book. Restrepo was the platoon medic who was killed in July 2007. The outpost was named after him. He was beloved by the men in the platoon, and his death was devastating to them.

Last month, I spoke with neurologist Dr. Aimee Chagnon who was packing for her second trip to Haiti to assist the victims of the horrific earthquake for World Wide Vision (WWV), a nongovernmental organization (NGO). Recently, I spoke with her after she returned from nearly three weeks in Haiti.

Northside S.F.: Paint us some word pictures of what you saw, how you felt when you got off the plane in Port au Prince?

Chagnon: When I got off the plane, I was struck with all the sensory memories that I’d kind of forgotten in the February trip, as most of it had been overwhelmed by the subsequent events of the trip. The heat, the humidity, and the sour smell hit me. The presence of heavily armed Haitian police was far more visible, while the various military organizations were not really there at all. The U.N. presence seemed to have been much smaller as well. When we finally got our luggage (I’d forgotten how stiflingly hot the baggage area was) and were waiting outside with the throngs of people, we heard someone calling to us – specifically calling to me. It was someone I’d worked with briefly in February, and he remembered me! It was touching and overwhelming to think in the face of the events that had befallen his country (and no doubt his family) over the past six months, and all the people he’d seen come and go, that he remembered me. Just one reason it’s so easy to fall in love with the Haitians.

The other thing that was immediately apparent was the total lack of change. The piles of rubble, the tent cities, the whole thing looked exactly the same as when I was there four months earlier.

Northside S.F.: What about the corruption? Has that gotten worse? It seems the corruption is recovering faster than almost everything else.

Chagnon: Every NGO has stories of things being held up in customs for lack of “paperwork” or proper “taxes” being paid. One of the groups involved with WWV, the RWH Foundation [founder of Alaska Structures and provider of the field hospital], bought a fuel trailer that would permit the hospital to have enough fuel to run for a week. As it stands, the hospital has to send personnel out each day to get diesel fuel, which is expensive, time consuming, and always risks running out because of shortfalls. The fuel trailer was bought several months ago and everyone kept getting the run-around about where it was, why it couldn’t be released, and we sent people to Port au Prince [a two- to three-hour trip each way] more than once to inquire directly. This is far from unique. I almost hate to tell the story because I don’t want to discourage people from contributing. A lot of NGOs can’t pay the extra fees, and CNN recently showed pictures of entire warehouses full of food, meds, and medical and construction supplies that had been sitting locked up for months – some cases almost since the quake itself.

We’ll have more with Dr. Chagnon next month.

Matt McFetridge is a two-time Emmy Award-winning television producer who has covered 20 wars in 20 countries over 20 years. E-mail:matt@northsidesf.com